Writing under ‘Nom de Plume’ in Latvia in the Period of Soviet Occupation

Author: Jānis Oga

19/10/2021

This blog article is based on my studies of the relationship dynamics between the most popular and recognized Latvian prose writers, known as the Soviet intelligentsia, and the occupation regime of the middle and late Soviet period (1968–1991) that partly overlaps the Stagnation Period (1964–1982). Usually, the attention of researchers is drawn to those individuals that are known as being openly dissident; however, in this article the focus has been shifted to writers recognized both by official critics and readers.

Nom de plume, also known as pen name and pseudonym, is a name that differs from an original orthonym (‘true name’) and is a new name that a person, usually a writer, an artist, or an actor, adopts for a particular purpose (Room 2010: 3). Several authors have reflected on pseudonyms. For example, Carmela Ciuraru, in her book Nom de Plume: A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms, writes that “[a] pseudonym may give a writer the necessary distance to speak honestly, but it can just as easily provide a license to lie” (Ciuraru 2011a: xix). Whereas Australian scholar Elizabeth Burns Coleman refers to the philosopher Lynne Tirrell who explains dynamic of the identity of a work through an ‘inferential role’ theory of meaning (Coleman 2004: 278) and accordingly claims that “the identification of what has been uttered, and the significance of that utterance, depends in part on the identity of the speaker” (Ibid: 279). Furthermore, Russian literary scholar Olga R. Demidova writes that the phenomenon of pseudonym “is treated philosophically from three different angles, i.e., those of a ‘play strategy’, as well as within the frames of the oppositions ‘freedom – non-freedom’, ‘the seeming – the real’ [..] At the levels of definitions, it is customary to consider a pseudonym in the same conceptual and terminological range with the concepts of ‘face’, ‘mask’, and the closely related ‘disguise’” (Demidova 2017: 122). Demidova also stresses that the use of a pseudonym is always a result of a conscious need, a pseudonym itself is the result of a conscious choice from several options; preference for one or several options is due to a complex of reasons, both internal and external. A pseudonym is a rather flexible tool of self-identification, directed inward and outward; it relates to the concept of a name at the symbolic and semiotic levels, confronting it on the one side and pushing off from it on the other(Ibid: 123–124).

Are any of these concepts useful in describing the role of pen names in the Soviet period? Alongside other aspects, noms de plume characterize the prose writers of the Stagnation period. After analysing statistics, broadly it can be claimed that most commonly pseudonyms were chosen by the writers born between 1910 and 1930 and making their debut in literature in the 1950s. Among the writers born in the next decade, in the 1930s, and publishing their first works in the 1960s, only a few prose writers adopted pseudonyms for their literary work.

This choice is possibly related to World War II as a dividing line. Especially for Latvian men who were drafted into the armies on both sides of the war, the post-war years offered to start the life anew. In the Stalin period, moreover, there was an illusion that in case of a failure – writing was a risky affair in the face of changing attitudes – a pseudonym would make it possible to protect the author’s family and distant relatives from repressions.

Adoption of pseudonyms is a long tradition that started as early as in the 16th century and continued in the pre-war period in Europe. Guillaume Apollinaire, Knut Hamsun, Anatole France, A. H. Tammsaare, and many others can be mentioned among those authors who wrote under a pseudonym. This tradition was also strong in Russian literature as evidenced by Anna Akhmatova, Arkady Gaidar, Maxim Gorky, Ilya Ilf, and Evgeny Petrov, not to mention politicians and statesmen like Lenin, Trotsky, and Stalin. Also, many outstanding Latvian poets and writers adopted pseudonyms since the National Awakening (Auseklis), especially in the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, for instance, Rainis, Aspazija, Edvards Virza, Edvards Treimanis-Zvārgulis, as well as during the World War I and the interwar period such as Aleksandrs Čaks, Jānis Sudrabkalns and others. However, many pseudonyms were used for certain publications in periodicals or books in most cases.

Jānis Oga, Dr. philol., is the post-doctoral researcher at the Institute of Literature, Folklore and Art of the University of Latvia. His doctoral thesis, Literary Translation and the Latvian and European Cultural Identity Formation: The Aspect of Creative Industries (2014), deals with the translations of fiction by Latvian writers in the second half of the 20th century, the institutions and persons responsible for the development of the translation field and the mobility of writers. Currently he is working on the monograph Latvian Prose Writers under the Soviet Occupation: Collaboration and Non-Violent Resistance (1968–1991).

Contact: janis.oga(at)lulfmi.lv

The situation of Latvia in the occupation regime has been directly linked to its geopolitical position. The Estonian scholar Epp Annus has introduced the concept of Western borderlands regarding the Baltic states. These were countries that “enjoyed the advantage of a still-active pre-Soviet cultural memory, in comparison with those lands where Sovietization processes started immediately in the post-revolutionary years: in the Western borderlands, a living memory kept alive continuities with pre-Soviet times” (Annus 2018: 240). The continuation of the tradition of adoption of pseudonyms in post-war Latvia is in line with Annus’ concept, though this is also one of the rare cases when it does not contradict Soviet modernity and even fits into it. A long comment would also be possible about the role of public letters, signed anonymously, collectively, or with nicknames, in the Soviet Union. Nevertheless, it is even said that “[a]ll ethnic literatures, created solely or largely by native speakers of the language in which they are written, are rich in noms de plume, some of them of great significance” (Wood 1977: 105).

Being an author in the USSR was a privilege, and it was also enshrined in the law. The Civil Code of the USSR and accordingly the Civil Code of the Latvian SSR stated that “the author has the rights: to publish, reproduce and distribute their works in all ways permitted by law under their own name, under a conventional name (pseudonym) or without a name (anonymously)” (Gilmanis 1979: 644). The Law also stipulated that “the author’s property and personal rights in a work published under a pseudonym or anonymously shall be protected by the organization which published, performed, or otherwise used the work until the author has made his real name known to the public” (Ibid: 647). The author’s rights to use a pseudonym is also confirmed by practice – in this case, in communication between official institutions. On May 12, 1981, Secretary of the Board of the Latvian SSR Writers’ Union Gunārs Cīrulis (also a pseudonym of the Jewish–Latvian writer Gabriels Civjans) addresses a letter to the head of the letter department of the daily newspaper Rīgas Balss (“The Voice of Rīga”, see Figure 1) with a copy to the Press Committee of the Latvian SSR (i.e. the Ministry of the Press), apparently in response to a complaint: “It is also clear that the choice of a literary pseudonym and its legal (financial) status is a personal matter for each writing citizen.” (NAL 1)

As an official, Gunārs Cīrulis signed this letter under a pseudonym. Among writers, pseudonyms and real names merged and sometimes were used in parallel or even formally changed in the passport. Although the law prescribed certain limited functions for the pseudonym, the pseudonym and the real name (a person) were not distinguished and received both privileges and sanctions, for instance, rights to additional living space or threat of prosecution.

Another example is a letter from December 22, 1971, written by the First Secretary of the Board of the Latvian SSR Writers’ Union Alberts Jansons (a real name) to Deputy Prime Minister of the Latvian SSR Viktors Krūmiņš and asking for support for “slight improvements in the issue of writers’ apartments” (NAL 2). All three writers mentioned – Ēvalds Vilks, Egons Līvs, and Alberts Bels – have adopted pseudonyms which are followed by real surnames in brackets, except the last one, because Alberts Bels, originally Jānis Cīrulis, had adopted his pseudonym for his real name in March 1971.

In her essay supporting her book mentioned above, Ciuraru also claims: “When the venerable tradition of the pseudonym is discussed, it is often in reductive terms. The other day, someone said to me, ‘There are three reasons why authors use pen names, right?’ and went on to cite them: Women writing as men. Writers with dirty secrets to hide. Highbrow writers slumming it in trashy genres. It’s true that each of those motives is historically common, but there are many others” (Ciuraru 2011b).

Latvian literary historian Ilgonis Bērsons who has compiled and published two volumes of Latvian pseudonyms entitled, literally, Pen Names and Pen Letters (Segvārdi un segburti), divides pen names into seven categories: “1) modifications of a person’s given name or surname, as well as given names and surnames (real names) for public or individual use; 2) names for which only surnames have been changed, as well as surnames for which only names have been changed (the new formation is one whole); 3) names (forenames) without surnames or surnames without names; 4) nicknames (open and secret); 5) approximate designations; 6) special signatures, especially in humorous literature; 7) literary images with strong prototype features” (Bērsons 2014: 5–6).

I divide Latvian writers who have used pseudonyms in the Soviet period, from the 1950s to the 1980s, into at least seven large groups: (1) writers who adopt a pseudonym for their creative work; the pseudonym and the real name merge until the pseudonym becomes the new real name, sometimes officially in the person’s identity documents; (2) writers who adopt a pseudonym for their creative activities for a limited time and return to the real name, usually in the early stage of the writer’s career or after ideological criticism and rehabilitation; (3) writers who are forced to adopt pseudonyms because the original name is too common, traditional, or identical to another famous writer’s name; (4) writers (mostly female) who adopt pseudonyms to distance themselves from former or existing marriages; (5) writers who adopt pseudonyms because of nationality, for example, Jewish and Russian writers writing in Latvian; (6) writers who, by pseudonyms, demarcate literary activities from another profession, such as a physician’s job; (7) humourists who adopt appropriate, often amusing pen names.

There are also several complicated and overlapping cases when a writer has acted under several names simultaneously, for example, a real name, a pseudonym, and a nickname of the KGB agent.

The selection of writers’ pseudonyms within the initiatives of the Latvian KGB has been described by the Latvian scholar Eva Eglāja-Kristsone in her book Iron Cutters. Cultural Contacts between Soviet Latvian and Latvian Exile Writers (Dzelzsgriezēji. Latvijas un Rietumu trimdas rakstnieku kontakti) as a part of “the infiltration of the exile press and the fabrication of newspapers or magazines ostensibly initiated and produced by the exiles themselves” (Eglāja-Kristsone 2013: 333). She stresses that the pseudonyms, used by some KGB authorities to pretend to represent exile writers, were “exaggerated Latvian and artificial constructs” and it was “an unenviable and even absurd task: to accept, in literature, a secret double identity, both by inventing a nom de plume, familiar to a very narrow circle, and by trying, as a Soviet citizen, to write from the point of view of an exile” (ibid: 117).

Also interesting, but outside the subject of this article, there are cases when a writer does not adopt a pseudonym, even if his or her surname is widely used, coincides with the name of another, often very famous writer, or in cases with other motivating circumstances for accepting a pseudonym, such as criminal record before debut in literature.

Now I will focus on just a few examples.

The merge of the pseudonym and the real name

Alberts Bels (born as Jānis Cīrulis in 1938). One of a few prosaists with a pseudonym among writers born in the 1930s. He debuted in 1963. As mentioned before, he adopted his pseudonym for his real name in March 1971. In an interview in 1988, Alberts Bels remembered:

“When I started writing, a professional writer [Gunārs] Cīrulis was already working in literature. In addition, at the post office, on request, letters addressed to me had been taken several times by another Jānis Cīrulis, and one of his letters was given to me. I have heard various legends about the choice of my writer’s name; now I will launch one myself. Putting the first letters of the next sentence together, you will read Baigi Ellīgs Latviešu Stāstnieks [Really Naughty Latvian Storyteller]. Bels. At that time, I only wrote short stories. Translations appeared. Then the mess began. I had to write myself a power of attorney to receive royalties. But the law’s assertion that the writer’s pseudonym provides some protection against attacks turned out to be fiction. [..] My writer’s name was on the list of great sins at that time. [Because of the unpublished novel ‘Insomnia’, 1967, a criminal case was filed against the writer. – J. O.] They tried to detach me from writing. Some people hoped that the writer Alberts Bels would disappear as it appeared, and Jānis Cīrulis would do some real work in Latvia. In the crossfire, I did not want to step back. Criminal proceedings were instituted against Insomnia. I needed to confirm my position somehow. I did this by anchoring my writer’s name, saying that I would not give up any of my literary works. I believe that in conjunction a name and a person, a person is the main thing” (Kalniņš 1988).

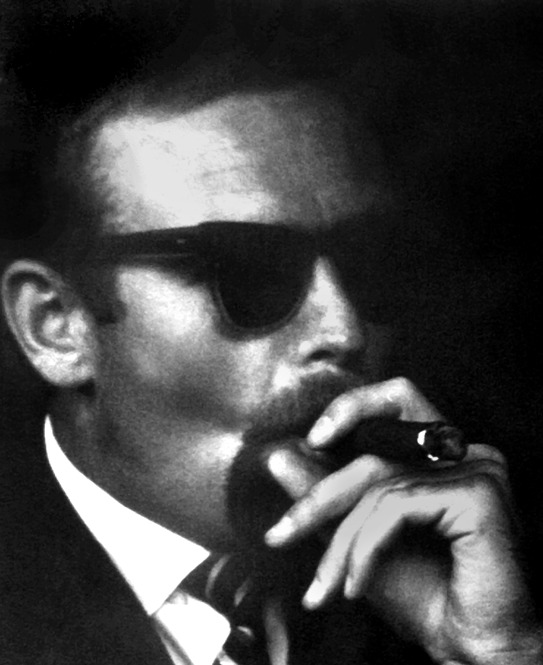

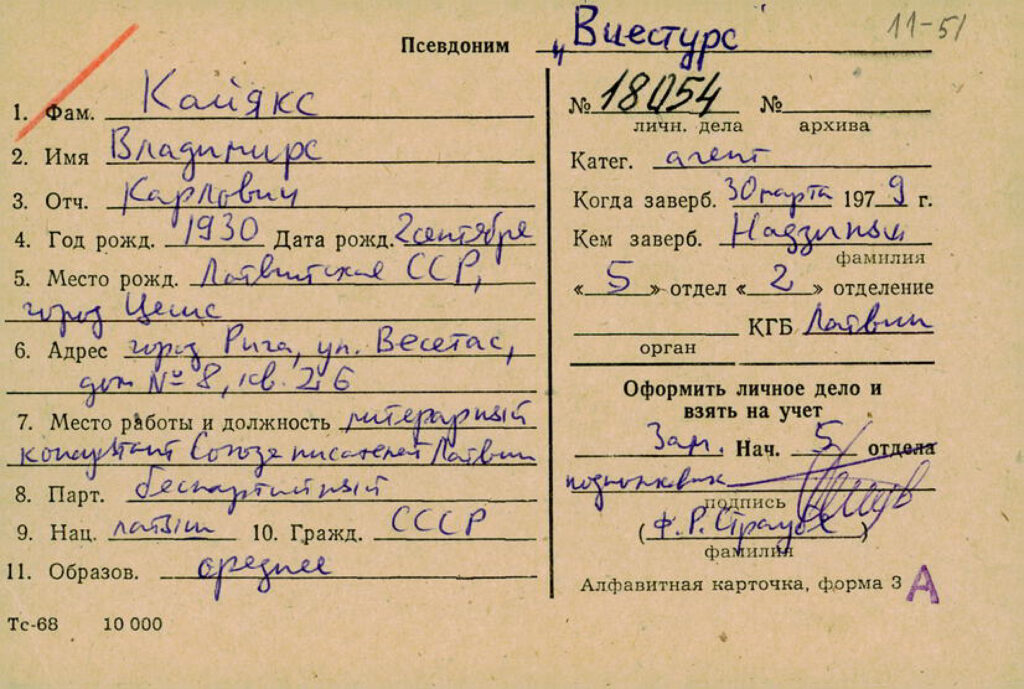

Vladimirs Kaijaks (1930–2013). One of the above-mentioned complicated cases. Real name – Kārlis Laimonis Lazdovskis (until 1959). He debuted in 1949 under a pseudonym Vladimirs Kaijaks. After the marriage with the poet Mirdza Bendrupe in 1959, he became Kārlis Bendrups (1959–1970), though continued to use his pen name in publications. After the divorce in 1970, he changed his name to the pseudonym and became Vladimirs Kaijaks officially. On March 14, 1979, Kaijaks started his work as a literary consultant at the Latvian SSR Writers’ Union (NAL 3). At the end of the month, on March 30, 1979, he became an agent for the Committee for State Security of the Latvian SSR, or KGB, with the nick name Viesturs (VDK ASK), working at the 5th department ‘against ideological diversion’ and its 2nd section – with creative intelligence as the object of his work (Zālīte 1999).

Return to the real name after adopting a pseudonym

Visvaldis Lāms (1923–1992). In 1943 he was mobilized in the Latvian Legion (a formation of the Nazi army during World War II), in 1946 released from the inspection and filtration camp. Lāms has devoted several of his works to the topic of legionnaires. He debuted in 1953. Following the publication of novels Baltā ūdensroze (White Water Lily, 1958) and Kāvu blāzmā (In the Aurora’s Glow, 1958) in literary journals, Lāms became the target of ideological criticism and was barred from publication for seven years. Until 1968, he published his works under the pseudonym Visvaldis Eglons.

A pseudonym to distance from former or existing marriages

Regīna Ezera (1930–2002), née Šamreto, married as Lasenberga, Kindzule (see Figure 4). Debuted in 1955. The choice of her pseudonym confirms both the attempt to distance herself from previous marriages and her current husband and careful search for a name that clearly confirms belonging to the national (Latvian) literature she represents. Additionally, she wanted to avoid bureaucracy that accompanies the change of name and surname. In 1999 Regīna Ezera remembered:

“At that time, there were considerations that in some cases, you want to hide a little. It is not easy to enter an official institution and introduce yourself as a writer. Although, when I started writing, I did not imagine that I would achieve anything. I had lived with my second husband, Kindzulis, for three years already, but I had not yet formally divorced my first husband, Lasenbergs. So naturally, this confusion of surnames prompted me to look for a pseudonym. In my passport, I was Lasenberga, living with Kindzulis. Well, I will not sign my works with the surname of the man I am going to divorce from. At the same time, it seemed awkward to me to sign up as Kindzule when I was officially Lasenberga. Well, I was able to return to Šamreto... But a Latvian writer – with such a last name! [..] And then even I would have to change my passport back, look for all sorts of papers... I do not have so much enthusiasm [..]. I have always liked the waters; I liked living by rivers and lakes. Call myself River [Upe] or something like that – Andrejs Upīts, Ernests Birznieks-Upītis already had that name. Bad again. To choose something like Marcinkēviča – quite crazy, I wanted something Latvian. This is how Ezera [Lake] came about.” (Berelis 2000: 7).

Image credit: A. Iļjina, “Latviešu rakstniecība biogrāfijās”, Rīga: Zinātne, 2003, literatura.lv

Latvian literary critic and writer Guntis Berelis writes that “[c]hoosing a pseudonym if the writer has decided on this step, however, is an important event in his biography. [..] The choice of a pseudonym is always based on some rational considerations – why this linguistic entity and not another [..]” (Berelis 2000: 7). We could perhaps agree with Zeynep Aslı, writing about Turkish journalist and novelist Server Bediî, who asks: “Couldn’t it be the nom de plume that chooses its author?”

To conclude, collaboration with the occupation regime and non-violent resistance is characterized by the choice, maintenance, or renunciation of a pseudonym, the convergence of a person and a pseudonym (when the pseudonym is formally adopted as a name in a passport), as well as by the poetics of pseudonyms – writers often adopted national, very Latvian pseudonyms, or, on the contrary, international, suitable for the Russian and international cultural environment. A detailed analysis will be offered in a scholarly publication.

References

Annus, Epp (2018). Soviet Postcolonial Studies: A View from the Western Borderlands. London/New York: Routledge.

Berelis, Guntis (2000). Regīna Ezera, prozas vecene, jeb Apmātība. Ezera, Regīna. Raksti trīs sējumos. 1. sējums. Rīga: Nordik.

Bērsons, Ilgonis (2014). Segvārdi un segburti. Noslēpumi un meklējumi. 1. grāmata. Rīga: Mansards.

Ciuraru, Carmela (2011a). Nom de Plume. A (Secret) History of Pseudonyms. HarperCollins.

Ciuraru, Carmela (2011b). The Rise and Fall of Pseudonyms. The New York Times, June 24.

Coleman, Elizabeth Burns (2004). Some Thoughts on Plagiarism, Forgery and the nom de plume. Dobrez, Livio; Jones, Jan Lloyd; Dobrez, Patricia (eds.). An ABC of Lying. Taking Stock in Interesting Times. Melbourne: Australian Scholarly.

Demidova, Olga R. (2017). Literaturnyj psevdonim kak fenomen kul’tury. Paradigma, No. 26.

Eglāja-Kristsone, Eva (2013). Dzelzsgriezēji. Latvijas un Rietumu trimdas rakstnieku kontakti. Rīga: LU Literatūras, folkloras un mākslas institūts.

Gilmanis, J. u. c. (1979). Latvijas PSR civilkodeksa komentāri. J. Vēbera vispārīgā redakcijā. Rīga: Liesma.

Kalniņš, Raitis (1988). “Baigi ellīgs latviešu stāstnieks”. Skola un Ģimene, No. 9.

NAL 1: The National Archives of Latvia, The State Historical Archive of Latvia, LNA LVA 473. f., 1. apr., 541. l., 6. lp.

NAL 2: The National Archives of Latvia, The State Historical Archive of Latvia, LNA LVA 473. f., 1. apr., 370. l., 52. lp.

NAL 3: The National Archives of Latvia, The State Historical Archive of Latvia, LNA LVA 473. f., 1. apr., 505. l., 76. lp.

Room, Adrian (2010). Dictionary of pseudonyms. Jefferson, North Carolina, and London: McFarland & Company.

VDK ASK: LPSR VDK aģentūras statistiskā kartotēka, LV_LVA_F1_US30_GV2-11_0051.

Wood, Richard E. (1977). Noms de Plume of Esperante Authors. Literary Onomastics Studies: Vol. 4, Article 10. Zālīte, Indulis (1999). LPSR VDK uzbūve un galvenie darba virzieni (1980.–1991. g.)

This article is a part of the ongoing postdoctoral research project “Latvian Prose Writers under the Soviet Occupation: Collaboration and Non-Violent Resistance (1968–1991)” (Nr. 1.1.1.2/VIAA/3/19/482).

Cite this article: Jānis Oga, “Writing under ‘Nom de Plume’ in Latvia in the Period of Soviet Occupation”, Blog4Dissent, October 19, 2021. https://nep4dissent.eu/janis-oga-writing-under-nom-de-plume-in-soviet-latvia/