An Aberrant Poser. Mikutis

Author: Odeta Žukauskienė

21/02/2022

An underground man

He was an enigmatic poser at the Academy of Art having a skinny and convulsive body. A mysterious person who recited by heart the poems by Pasternak, Trakl, Goethe, Holderlin, Rilke, Cvetajeva to name just a few. He was a regular visitor in artists’ studios, homes and informal places. A solitary thinker who spoke mostly in a monologue and whose fragmentary language was full of paradoxical associations and free knowledge. He was a vagrant hermit wandering around Vilnius and out of town, completely detached from household and societal standards. He gained respect from artists and intellectuals, as well as experienced alienation and abandonment. He was tormented by the bustle of thoughts and spent quite a bit of time in a mental hospital…

The answer to the question who was Justinas Mikutis, is not simple. It is possible to fall into the traps of heroization, creating a lovely legend of the uncompromising person. And it is possible to slip in the other direction, focusing on his marginality that led to self-destruction, thus overlooking the real significance of his presence in cultural life. Perhaps the question – who was Mikutis? – can be answered in his own words about poet Paulius Širvys: “Whoever he was, he was real“. His life and destiny encompass many aspects that are difficult to filter out and extract from a complex picture of reality.

In any case, as an (in)visible underground man, nicknamed Pelys (Mice), Mikutis serves us as a certain key to the so-called “Silent modernism”. [1] A small fragment from Justin Mikutis’ notes is published in the book dedicated to this phenomenon in Lithuanian culture which is written as a supplement to his reflection on the metaphysical truths about human existence delving into the analysis of an elusive character of Stavrogin from Dostoevsky’s “Demons”. That passage accurately reflects Justinas’ style of internal-literature-related and constantly cracking thought with deep insights into the laws of morality and creation. [2] Recently “Silent modernism” has been reconsidered expanding its dichotomous definitions and the perception of quietness and shadowiness. [3] Although even after revealing the diversity of systemic, non-systemic and anti-systemic segments [4], Mikutis’ figure remains distinctive in that he questioned the very project of modernity, did not acknowledge any clichés and completely rejected secular totalitarianism. And his mode of being has become a radical contrast to the system, in which he lived solving existential dilemmas on his own.

Beyond the facts

A literary critic, thinker, mystic and political prisoner of the Soviet gulag Justinas Mikutis (1922–1988) has remained in the memories of many Lithuanian artists as a master of authentic speech and an absolute nonconformist. In 1941 he graduated from the Kretinga’ Franciscan Gymnasium where he became particularly interested in German literature. In 1942, he entered the Faculty of Philosophy of the Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas to study literature, immersing in existentialism. After the university was closed in 1945, he returned to teach in his native Žemaitija, but was soon arrested by the NKVD on suspicion of participating in an underground national organization, sentenced to 10 years imprisonment and deported to the Uchta and Vorkuta camps in Siberia.

The horrors of reality brought him to the philosophy of tragedy, but he never loosed his faith and a “divine radiance”. In a sense, he deepened his thinking in conversations with camp inmates. Horst Bienek (1930–1990) – Silesia born German novelist, poet and filmmaker – was one of his companions in the Vorkuta labour camp who, after an amnesty, described the brutal experiences in his writings. Among the disputants was also German psychologist Sigurd Binski (1921–1993) who documented the inhuman life in concentration camps in his Zwischen Waldheim und Workuta (“Between Waldheim and Vorkuta”), published in 1967. Mikutis was close to many of those “victims with dignity” – Russian and non-Russian intellectuals, artists, professors and students.

Having the opportunity, he tried to escape from Vorkuta with a few prisoners, but his comrades were shot dead and he was littered with dogs. The accident crippled him; in 1956 he was released due to poor health. After returning to Vilnius, he was confronted with the absurd reality of socialist welfare. He was employed in the factory as an elevator worker and for a while served as a translator of technical texts. The proletarian environment was unbearable. He was spooning around Vilnius looking for someone to talk to, someone to share his thoughts with.

The career of the poser

In 1957 invited by painter Arvydas Šaltenis Mikutis began posing at the Vilnius Art School, later at Vilnius Academy of Arts (1957–1961, 1975–1981), previously State Art Institute, so he became an informal educator. Mikutis received one ruble for an hour of posing and thus could survive. Posing and during breaks, he discussed with the students, immersing himself in topics interested him. In his talks on philosophy, poetry, art, history and religion, he demanded to his listeners to delve into the essence of being human and the essence of art. He was a charismatic figure and became an unofficial educator, presenting unusual considerations about art, aesthetics, and literature. His spontaneous and mysterious personality naturally aroused interest. His extraordinary memory, ability to quote psalms and poems, literary and philosophical works in original languages raised great respect for him.

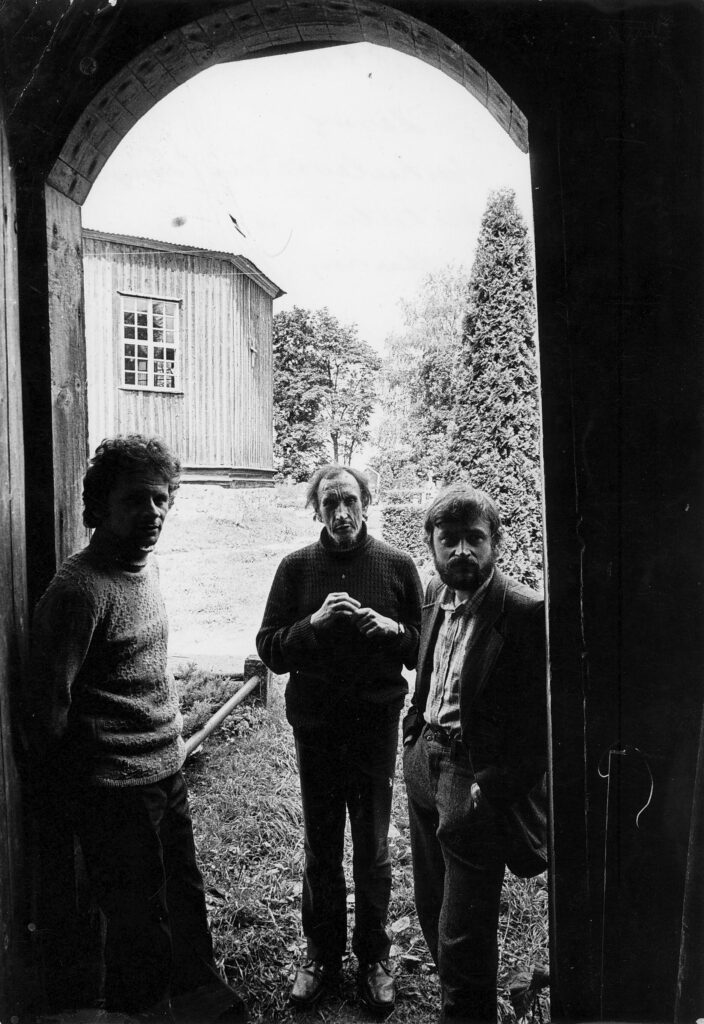

Mikutis was a frequent visitor to the art student’s dormitory, various gatherings of disobedient artists; he was a participant in summer camps (organized by art institutions at that time) and a long-term guest at artist’s homesteads. Many testify that his speeches were like philosophical performance that featured brilliant flashes of thoughts. As a man of intellectual spirit, he was constantly moving in the structures of his thinking, originally interpreting literature and visual art. He peculiarly explained the history of art, the sacredness of art, the essence of poetry, the themes of existentialist philosophy and Scripture, encouraging freedom of thought.

Occasionally he was going with students and artists to visit exhibitions, as well as to meet Gulag inmates and dissidents in Moscow and St. Petersburg. His friend, Chuvash and Russian poet Gennady Aigi shares his memories in the documentary “Gooseberry Wine, or a Film about Justinas Mikutis” [5] about Mikutis’ arrivals in Moscow where the whole camp company gathered for close conversation and a drink. He was always curious to listen to but he spoke mostly in monologue immersing in the flow of his consciousness. Several generations of painters have experienced the power of his presence nearby. So-called Vildžiūnas generation, Kuras or Šaltenis generation (otherwise known as “the break generation”) and younger generation (a big impact he made on painters – A. Stankutė, E. Velaniškytė, J. Maldžiūnas, A. Vaitkūnas, E. Varkulevičius-Varkalas, V. Žukas). “The young painters shared accommodation and bread with him, travelled together and, most importantly, listened to his missionary philosophical reflections and poetry recited in Lithuanian, German and Russian.“ [6] Therefore then the signs of conformism appeared in their live and creative practice, Mikutis sought the other company and retreated into solitude. According to Eglė Velaniškytė, he was like a litmus test. [7]

Mikutis lived a nomadic life. He was dangerous to the totalitarian regime because of his lifestyle and thinking, and therefore he was not always welcomed at the Academy of Arts. This way of life was characteristic of a particular social stratum. The word “bomž” was coined to describe the person “bez opredelionnogo mesta žitelstva” (without a specific place of residence). A Soviet citizen was required to register his place of residence, and those who did not have such a place would automatically fall out of the system. “That social stratum came from various types of “outcasts” – former prisoners, incapacitated people, who survived various failures in life. Young artists and intellectuals also joined it for a longer or shorter period of time – wandering and dressing had become even a special sign of free life or free creation. <…> The Nobel Prize-winning Russian poet Joseph Brodsky has described the experience of such wanderings in his poems and memoirs. It is worth noting that the Soviet “bomž” was very different from the current one” [8].

Features of thinking

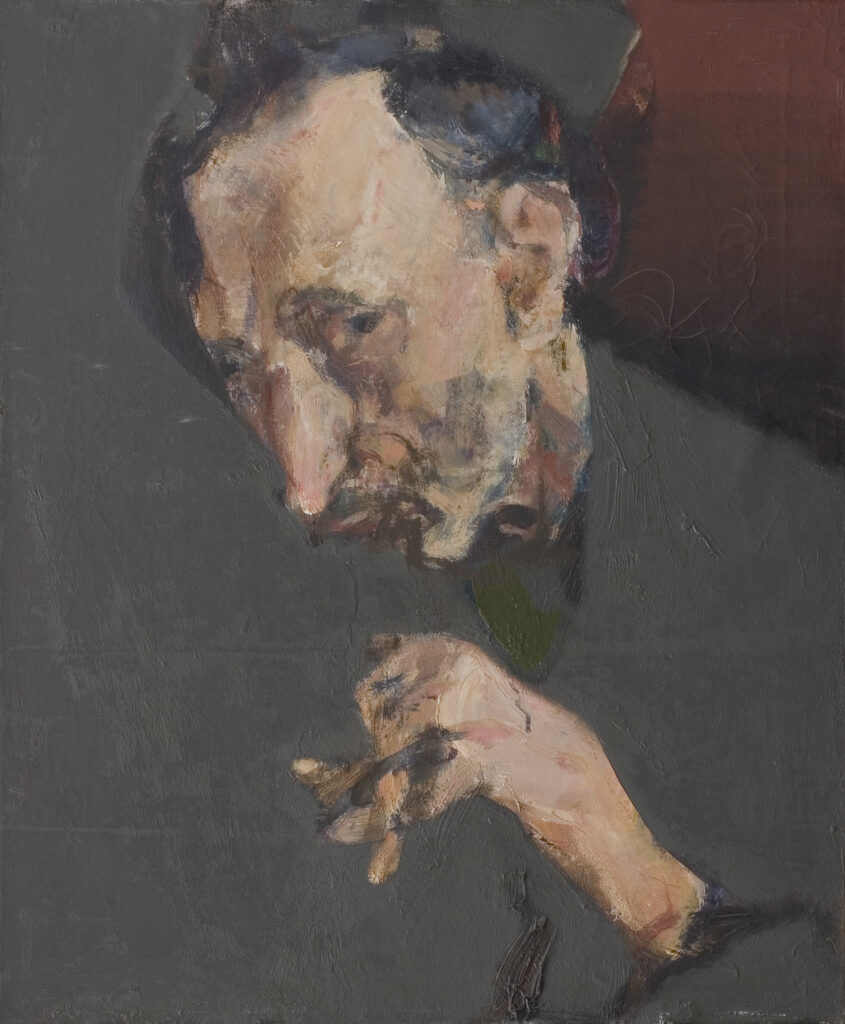

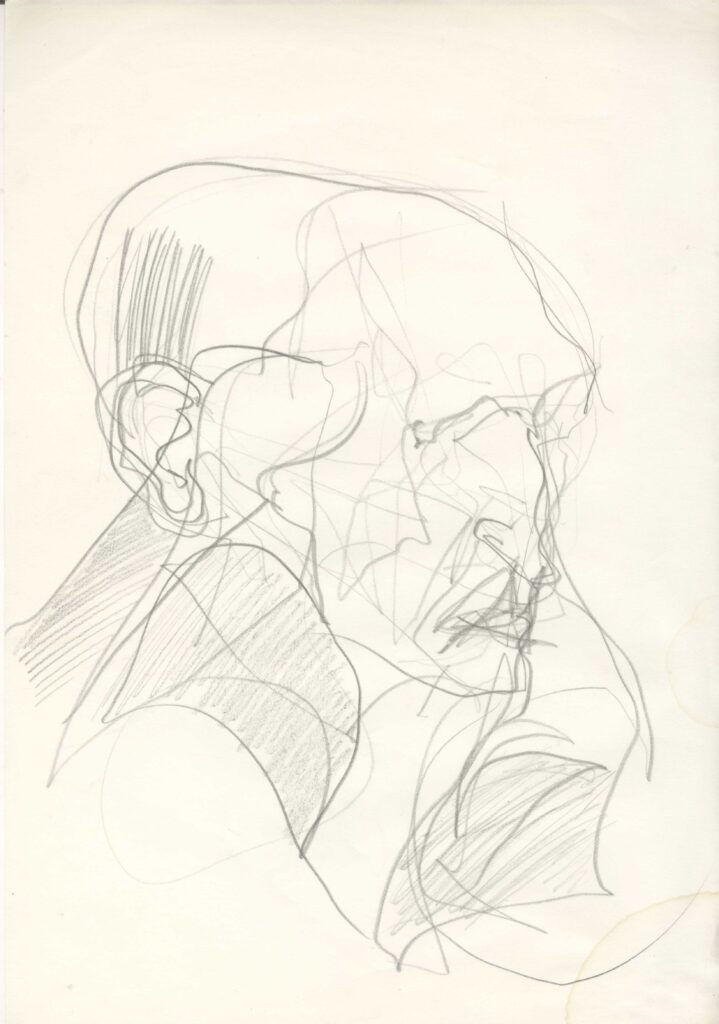

Reconstructing Mikutis’ thinking is not an easy task. After his death, the little fragments of his notes which do not have any coherent structure, have been published in the first years after declaring independence. They were prepared by the painter Vaidotas Žukas from the notebooks left by Mikutis. Some artists have preserved his speeches, recorded on tape. Many artists with whom he interacted refer to Mikutis in their memories, emphasizing their presence together rather than the impact of a particular thought. Certainly, he is immortalised in many works of art as an extraordinary poser. But more important is the invisible influence he has left on very different creative paths, which remains elusive.

Mikutis’ worldview was based on existentialist philosophy. In his words, “existentialism, in general, is a worldview that does not give a person the right not to believe, but neither does it give him the opportunity to believe.” [9] His philosophizing was based on life itself, a lively conversation, speaking related to specific situations, never finished and open for further reflection. He closely linked philosophy to the life of the individual and to his own personal tragedy. He can be seen as an existential phenomenologist whose thoughts resonate with his teacher Lev Karsavin and Russian existential thinkers Nikolaj Berdiajev and Lev Shestov. He similarly focused on divinity, free will and suffering, love and evil. He believed in the active spirit of Christianity. He admired the philosophy of Pascal, Kierkegaard, and Nietzsche, and analysed the literary works of Dostoevsky and Camus full of philosophical tensions and absurd experiences. His thinking was fused with philology. He referred to the literary works of Lithuanian and Polish writers, as well as to Proust, Pasternak, Joyce, Kafka and Folkner. But his greatest support was poetry, which he saw as the highest form of creation, in which everything could be united in one generalized formula.

In his notes “About God and Man” written in 1965–1967, Mikutis considers the metaphysical struggles of evil and good, concluding with the reflection on freedom: “Life is only “truth” (sarcastic in the sense of those quotes), or it is “freedom” (extremely sarcastic in the sense of quotes). Conclusion – life is a lie. But it takes inhuman strength to accept life as “truth” and “freedom” – in the sense of poetic conditional quotes. Only then will you be forced to accept that “truth” (freedom!) as the “truth” becoming truth or “freedom” as freedom.” [10]

In his writings of 1975–1980, he reflects on human value and creation as an existential form that redeems the real reality and in which the idea of divine creation can be discovered. He argues that the essence of the creative act is the ability to create a certain dramatic tension arising from the creative state of existence. “The most essential art in human creation, however, is a worldview.” [11] Moreover, not only the aesthetic taste is important, but also the “aesthetic morality”, which cannot be shaken with or separated from “ethical morality”. [12] Another important thing in art life, according to him, is spirituality. But “in order to embody spirituality in art, one needs to have it”. [13]

Many artists have memorized J. Mikutis’ words “accurate failure”. He used that expression to discuss both literary and visual works when he felt that there were certain profound metaphors. In fact, Mikutis looked at visual artworks more as a means of philosophizing, without going too deep into the formal language of an individual artist. He appreciated a certain contradiction, a paradox in art, when “completeness is achieved through incompleteness”, which causes intense vitality and ontological tension. “Art is a perfect failure” [14], he used to say.

In the memory of Vaitkūnienė and Vaitkūnas

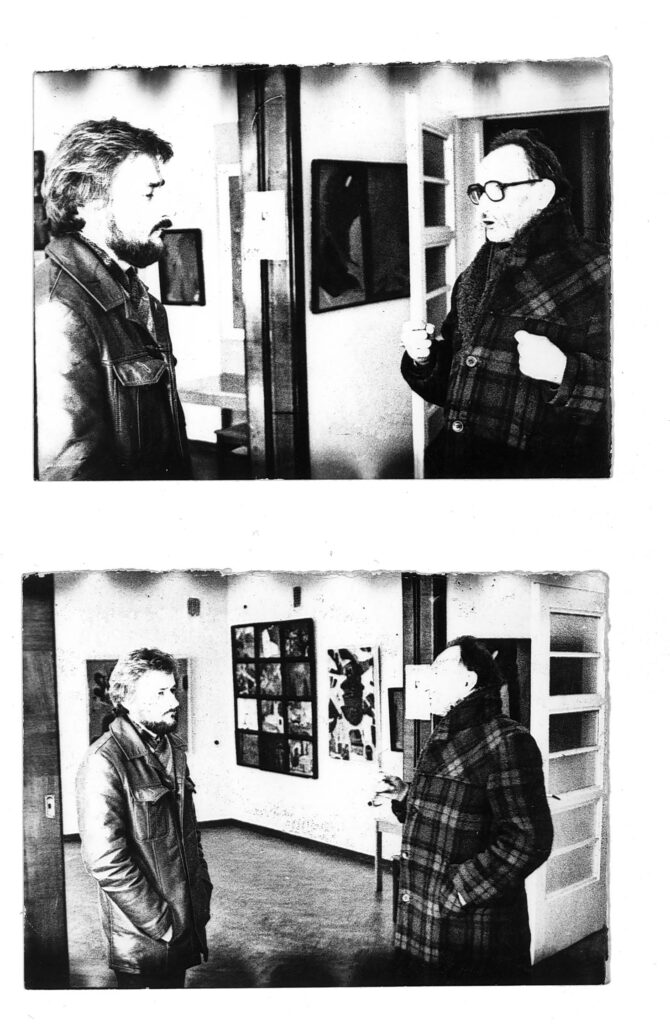

In early 2021, I contacted Aušra Vaitkūnienė, and she agreed to share her memories of Mikutis, as well as her husband’s Arūnas (who interacted more closely with Mikutis) works and photos from personal archive. Aušra enrolled to study painting at the State Art Institute in 1980 when Mikutis no longer posed there. She remembers the strange atmosphere of the time: “Everything is half-spoken, secrets kept hidden, Aesopian language, a life surrounded by fog. <…> the strict system and the fear of being expelled from the school forced to existence quietly. We compensated for this quietness by sitting, talking and sipping wine in the dormitory on Cvirkos Street. Young and old gathered here. In our nightly conversations, I heard about Mikutis, the legendary poser and guru of artists. I realized that the door to the institute for him was slammed shut by the rector.”

However, Aušra met him several times. Once, during the days of student art shows, when students held exhibitions in the corridors of the institute. It was 1982 or 1983 when she saw a group of students surrounded by an expressive, gesturing and loud-speaking person: “I realized it was the famous Mikutis. I approached him and listened. I had never heard such speaking; it was new and deeply shocking. He talked about painting, compared it to poetry and touched very deep layers. I didn’t understand everything, maybe because of my young age or ignorance of certain things. I deeply felt, my intuition whispering to me that this is true, something essential and real, what is hidden from us. A hidden reality had been uncovered.” His performance made an impact, revealing deeper meanings.

A deformed figure of Mikutis has rarely appeared in the corridors of the Institute in the 1980s. Aušra’s next encounter with him took place at a gathering of like-minded painters in someone’s studio. Mikutis (as it was usual) has joined while going. She remembers that it was a cold spring evening, but the wine and conversations warmed the atmosphere: “We talked about painting, existence, and the system. Mikutis, as always, recited poetry. Maybe poetry or other imagery turned the conversation into mystical things that impressed me a lot. It was the case that last autumn, in 1983, I buried my dad. This loss was unexpected, but it gave me a mystical experience I told no one about. Maybe it was the wine or the energetically rich environment that prompted me to tell Mikutis about this mystical experience, and I got confirmation from him that it was real… Mikutis told me about his experience of being in exile in Siberia. While working in the underground mines, he heard the voice of his dead mother, ordering him to flee the place as soon as possible. He climbed to the surface arbitrarily, and the mine collapsed right here… Even wine could not quench the inner tremor… the talking turned into movements, the dancing started… I danced with Justinas almost all night, still thinking about the fragility of life.” In her words, “it seems that his mission was to reveal to others the veiled meanings of life.”

The presence of Mikus created more than one person. He left a deep imprint on the creative path of Arūnas Vaikūnas. As a wandering sage, Mikutis walked with him and other painters around Samogitia and other parts of Lithuania, visiting sacred places. They travelled on foot, staying overnight in the woods or at the homes of ordinary people. The wandering was an important existential experience and a way of self-discovery.

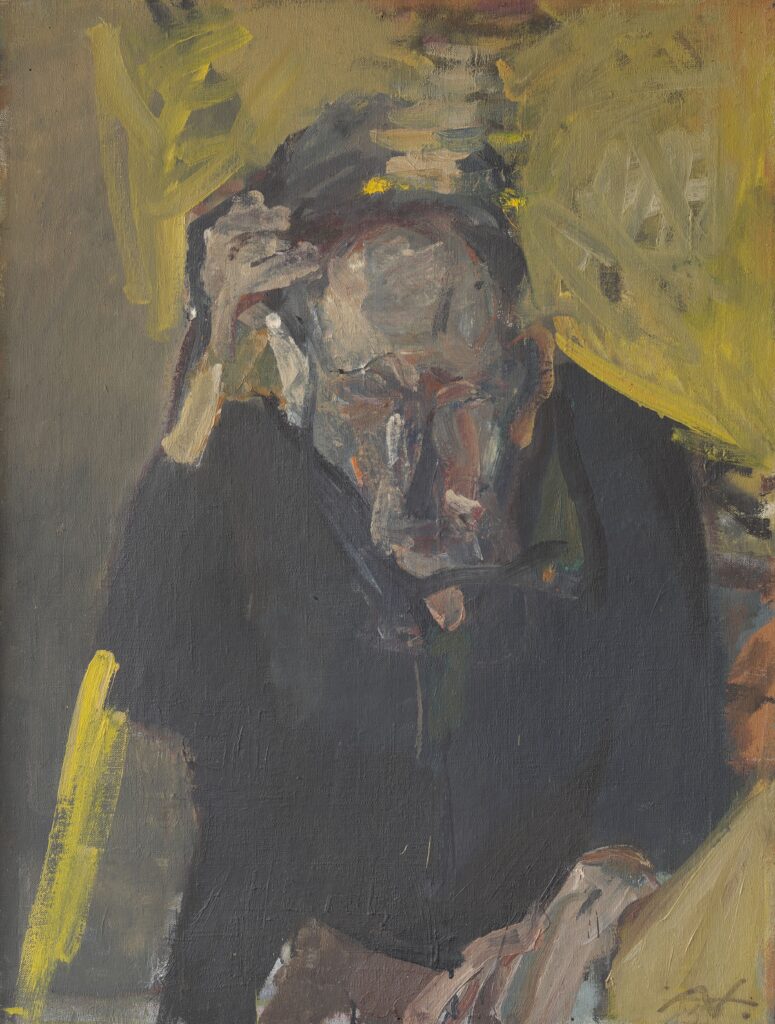

At the beginning of the 1980s, Vaitkūnas painted several psychological portraits of Justinas, who lived in his studio for a while, drinking wine and talking. Vaitkūnas described their communion: “It was like he was saying something, and I can’t really answer anything because he knew a lot more, and he was talking about high matters. Strange communication when you’re not the right talker. But when you draw, the communication is getting quite normal – he makes his thing, and I do mine.”

In fine

Mikutis befriended many artists, poets, writers, musicians, many of whom regarded him as an authority, teacher, and prophet. In the book “The Fourth Dimension: Art as a Form of Spiritual Energy” (1998) [16], Tomas Sakalauskas reflects on the different destinies of two peers, Mončys and Mikutis, encouraging the reflection of his role in dissent culture.

Much like Hölderlin, Mikutis believed that conversation makes us humans. Human existence is based on conversation, on talking and listening to each other. Conversation binds us with invisible threads. Sigitas Geda, a friend of the Mice, reflects those invisible threads in one conversation, “Petras Repšys once said about our youth authority Justinas Mikutis: what do you remember from him, only one or two phrases!” [17], but still, they somehow remain in the culture. On 9 July 1988 speaking at a rally in Vingis Park, Geda recalled the wisdom of the Indian tale about the little mice and the big elephant: “A mice will never defeat an elephant, but at a crucial moment, it can crawl into a ravine to tickle so that this swollen toad will start to sneeze terribly.” [18]

Odeta Žukauskienė is a senior researcher in the department of Comparative Cultural Studies at the Lithuanian Culture Research Institute. She also is an associate professor of art theory at the Vilnius Academy of Art, Kaunas Faculty. Her scientific interests include Contemporary Cultural Studies, Art History, Visual Arts and Cultural Memory. Her current research focuses on art, memory and visual culture in the 20th/21st centuries.

[1] The Silent modernism is a metaphor for the creative process and creative life. The metaphor has been described in: Tylusis modernizmas, ed. by Elona Lubytė. Vilnius: Tyto alba, 1997. [2] Justinas Mikutis, Tekstai sau, in: Tylusis modernizmas, 1997, p. 130. [3] Ar buvo tylusis modernizmas Lietuvoje? / Was there a quiet modernism in Lithuania? Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis. Ed. by Elona Lubytė. Vol. 95, 2019.

[4] Arūnas Streikus, Kas tildė modernizmą? Apie dailės lauko ypatumus sovietiniuose Vakaruose / What Made Modernism so Quiet? The Particularities of the Art Field in the Soviet West, Acta Academiae Artium Vilnensis. Ed. by Elona Lubytė. Vol. 95, 2019, p. 14–28.

[5] Agrastų vynas arba filmas apie Justiną Mikutį / Gooseberry Wine, or a Film about Justinas Mikutis by Ramunė Kudzmanaitė, documentary video film, 120 min., 1991.

[6] Raminta Jurėnaitė, Arūnas Vaitkūnas. Tapyba. Vilnius: Vilniaus dailės akademijos leidykla, 2012, p. 36.

[7] Mikutis communicated with Vincas Kisarauskas and Saulė Kisarauskienė, Algimantas Švėgžda, Algirdas Steponavičius, Vladas Vildžiūnas, Petras Repšys and many others. He interacted with Juozas Keliuotis, the editor of Naujoji Romuva, and the art historian Petras Juodelis. He lived with artists in camps in Beržoras, Dovainonys, Markučiai, in the homestead of Vilius Orvidas, and other places.

[8] Vytautas Rubavičius, Laisvės kelio ratas: Lietuva – Himalajai, in Paulius Normantas. Kelionės į tolumas, ėjimas į save, sudaryt. O. Žukauskienė. Vilnius: Lietuvos kultūros tyrimų instituto leidykla, 2019, p. 99.

[9] Justinas Mikutis, Padrikos mintys apie amžinus dalykus. Parengė Vaidotas Žukas, Veidai’88. Jaunųjų kūrybos almanachas, Vilnius: Vaga, 1989, p. 210.

[10] Justinas Mikutis, Apie Dievą ir žmogų (1965–1967), Šiaurės Atėnai, 1992, Nr. 18 (113), p. 4.

[11] Justinas Mikutis, Poetinis kūrybos aktas, Poezijos pavasaris’89. Vilnius: Vaga, 1989, p. 314.

[12] Ibid. p. 315.

[13] Justinas Mikutis, Padrikos mintys apie amžinus dalykus. Veidai’88. Jaunųjų kūrybos almanachas, 1989, p. 210.

[14] "Menas yra taiklus nepataikymas".

[15] Aušra Vaitkūnienė, Arūnui Vaitkūnui atminti. Portretai, www.kamane.lt, 2008-01-15.

[16] Tomas Sakalauskas, Ketvirtoji dimensija: prologas, septynios dalys ir epilogas: Mončys: skulptorius; Mikutis: mąstytojas; menas: dvasinės energijos forma. Vilnius: Alma littera, 1998.

[17] Sigitas Parulskis, S. Geda: jau visi esame benamiai, mums liko tik prisiminimai, LRT Radijo laida „Kultūros savaitė“, LRT.lt. 2013-02-11.

[18] Sigitas Geda, Žodis Lietuvai, Lietuvos politinės minties antologija III. Politinė mintis Lietuvoje 1940–1990. Vilnius: Vilniaus universiteto leidykla, 2013, p. 313–314.

Cite this article: Odeta Žukauskienė, “An Aberrant Poser. Mikutis”, Blog4Dissent, February 21, 2022. https://nep4dissent.eu/odeta-zukauskiene-an-amberrant-poser-mikutis