HIDDEN GALLERIES: Interview with James Kapaló. Part 1

The interview was carried out by Sanita Reinsone as an e-mail conversation from 7 July to 18 August 2021, without any haste or length limit.

23/08/2021

This year marks the end of the ERC Hidden Galleries project which ran for the last 4 and a half years. I've been following it with great interest; it especially attracted my attention due to its powerful visual stories. Could you introduce yourself, your team and give a background of the Hidden Galleries project – how it came about, what is its thematic and geographic scope?

My name is James Kapaló and since 2016 I have been Principal Investigator of the Hidden Galleries project. I am a scholar of religions based at University College Cork in Ireland and during my career I have been concerned mainly with the history and ethnography of religious minority communities in Romania and the Republic of Moldova. Personal biography often plays a part in our formation as scholars and for me growing up in the UK the son of a Hungarian 1956 refugee and spending my teenage years in the 1980s travelling across the Iron Curtain to spend time in a small, isolated village in North-Eastern Hungary with my relatives left me with vivid impressions of village religious life in the closing years of communism. From here also stems my interest in religious diversity, my father was part of the small Greek Catholic community of Ruthenian origin in a village that also had Roman Catholic and Calvinist Reformed parishes. My grandmother, a Roman Catholic, spoke fluent Slovak but had a Hungarian identity. This combination of linguistic, ethnic and religious identities in the microcosm of a remote village fascinated me and probably explains why I went on to conduct ethnographic fieldwork amongst minority groups such as the Hungarian Csángós in Romania and the Orthodox Christian, Turkish-speaking Gagauz of Moldova. Only more recently, however, has my research led me to explore these groups experience of surveillance and repression during communism.

From about 2013 onwards, whilst preparing to write a monograph about the Inochentist religious movement in Moldova, I began to engage with more archival research. Because I was relatively new to archival work at the time and came to it with an ethnographer’s eye, I think I was met with many surprises, especially once I started to explore the archives of the police and secret police in first Romania and then Moldova.

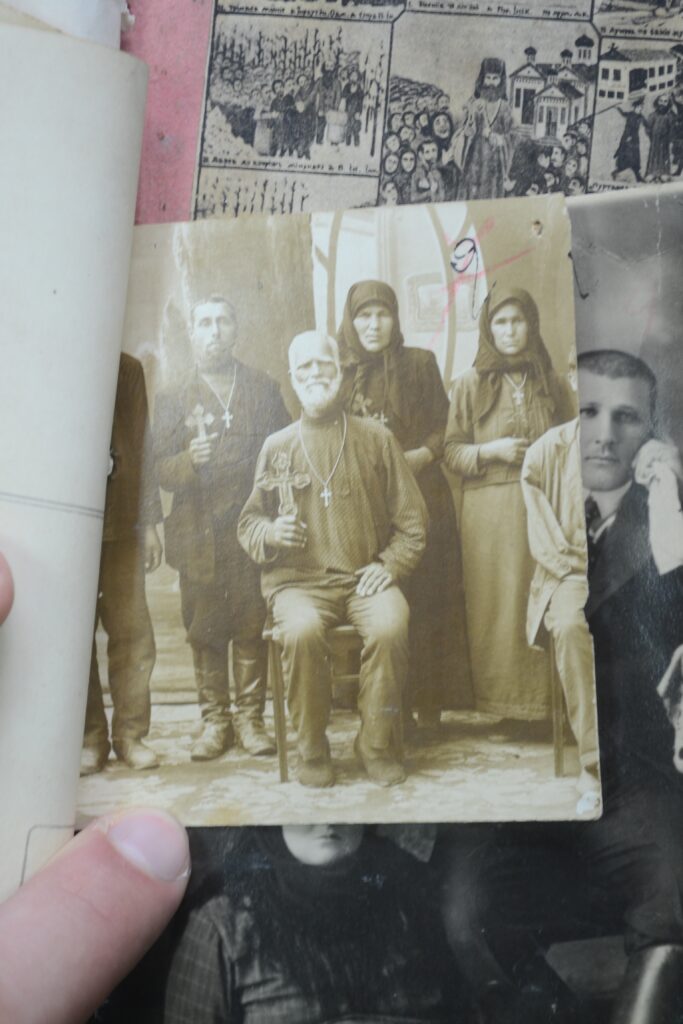

The idea for the Hidden Galleries project started with a set of confiscated photographs, not dissimilar to the ones shown here (Figure 1), that I came across in a file compiled by the Romanian gendarmerie in the Romanian National Archive. The file contained photographs and devotional postcard-style icons confiscated from a religious community that had been hiding in an underground church. As I reflected on the archives and the way that the history of groups repressed by authoritarian regimes have tended to be written, and as I read the description of the gender, ages and physical state of the 42 people arrested in the underground dug-out church, the objects, books and images stolen from them had a powerful impact on me. I turned the pages of the file slowly, touching the things that they had treasured, and sharing in the material and visual experiences that had been part of their lives.

As a researcher more used to ethnographic fieldwork, this small collection of worn, slightly frayed images demonstrated how the material religious dimension of the archive’s holdings, represented a meeting place of social actors, of embodied and material agencies that have been relatively overlooked in scholarship on religions during communism. I had felt a discomfort with frame through which Soviet and communist-era archives were being interpreted, an approach that insisted that secret archives, and especially secret police materials, could do little more than tell us about regimes of power or the construction of the enemy. This was a concern shared by Sonja Luhrmann in Religion in Secular Archives, where she insisted that it is possible to “pierce through” the layers of “rhetoric and standard formulae” in Soviet documents to “filter out facts” about religious life (2015, 3), she explicitly rejected the idea that communist archives speak “only of the internal workings of Soviet state bureaucracies.” The Hidden Galleries project grew from this recognition that “a record may be created for one purpose but used for other ends” (Zeitlyn 2012, 463), and that the archive can become the means by which “traces” that were never intended to form conscious historical remains can bear witness in the future.

My frustration with the discursive and constructionist approaches to the archives was matched by a frustration with most histories of religion under communism that focused on the fate and careers of bishops, patriarchs and pastors and their institutions and that tended to ignore the experience of ordinary believers and grassroots communities. As I came across more and more material traces of religion, confiscated items – such as diaries, photos, hymn sheets, icons and holy cards – but also maps, graphs and photographs produced by the security services that captured communities for the files, I began to also think about questions of access and ownership of these stolen aspects of cultural patrimony. Taking images and objects back to descendent communities became an important methodological pillar of the project, engaging communities as participants in the re-examination, re-contextualisation, and the re-telling of their past. Through archival work, fieldwork with communities, and exhibition making, both live and digital, the project has aimed to integrate the voices, ideas and experiences of communities into our materially inspired re-telling of the repression of religion during communism.

So from this starting point, the idea for the Hidden Galleries project came together, and over the past four and half years, with a the team of postdoctoral and PhD scholars from Romania, Hungary and the Republic of Moldova, we have recovered hundreds of images, objects and stories from thousands of mainly secret police, gendarme and police files. The research team consisted of Dr Kinga Povedák, an ethnologist of religion from Szeged in Hungary who worked mainly on underground protestant communities in Hungary, Dr Anca Șincan, a historian of religion in Romania during communism from Târgu Mureș who worked on Old Calendarist and Greek Catholic communities, Dr Ágnes Hesz, an ethnologist of religion who worked both on Hungarian materials as well as on the Hungarian minority in Romania, Dr Igor Cașu, who contributed invaluable expertise on and sources from the Moldovan archival collections, and Iuliana Cindrea and Dumitru Lisnic, who worked on Romanian and Moldovan minority religious communities respectively, and finally, Dr Gabriela Nicolescu, our project curator who also brought her anthropological training to enrich the project. We were extremely fortunate to have the opportunity to work closely with Dr Tatiana Vagramenko, who secured Irish Research Council postdoctoral funding to work in parallel with the Hidden Galleries team on a cognate project on Ukrainian materials.

Together we have explored the intersection of the secret police and their archives with lived religion in Romania, Moldova, Hungary and Ukraine along multiple axes. The project has not taken a programmatic approach, diverse methods and theories have been applied by the team, but we have consciously injected the concerns and questions of religions scholars into the debates on secret police archives and their meaning and uses, debates that have largely been dominated by historians and political scientists.

James Kapaló is Senior Lecturer in the Study of Religions at University College Cork, Ireland and co-Director of the Marginalised and Endangered Worldviews Study Centre (MEWSC). He has an MA in Central and Eastern European Studies from the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES), London and a PhD in the Study of Religions from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London. A specialist on religious minorities, his work draws on anthropology, folklore and history. He is Principal Investigator of the ERC Project Creative Agency and Religious Minorities: Hidden Galleries in the Secret Police Archives in Central and Eastern Europe (Project no. 677355).

Why did you choose to concentrate on religious minorities in your project? Do they have a different fate than the largest religious denominations in relation to the secret police activities and their archives?

The project was originally framed around the category of religious minority for a few reasons, one of which being the ongoing fate of some groups that have continued to be the target of state repression and widespread prejudice in post-communist societies. The Jehovah’s Witnesses are an obvious example. We hoped that by engaging with groups that remain, in some sense, on the margins of society today we would be able to incorporate their experiences into a more holistic understanding of history that would also inform contemporary problems faced by religious others in societies dominated by resurgent mainstream or national churches.

Another simple reason for the choice was the fact that mainstream churches have a lot of resources at their disposal, and often also have some degree of political influence, which means they have been able to effectively represent and catalogue their experience at the hands of both communist and fascist dictatorships. But ultimately, as we conducted our research, an alternative and the more salient category of analysis emerged, that of the ‘religious underground’. This term, widely used by both the Soviet authorities and the Western press before and during the Cold War, proved an extremely interesting lens through which to explore both minority religions and the dissenting movements that took shape within mainstream churches such as the Russian and Romanian Orthodox Churches and the Roman Catholic Church. So, in the end the project became more inclusive of a diversity of groups labelled as dangerous due to their underground activities and whose practices, material culture and worldview were shaped by their experience of repression and secrecy.

Using the term ‘gallery’ in the context of secret police archives might seem extraordinary or even controversial. ‘Gallery’ involves at least three dimensions – objects to exhibit, curators, and spectators. Once I interviewed a woman who spent nine years in the forest after WWII and then another seven years in Gulag. After the interview, I was exploring the files of her criminal case and came upon a photo of her taken in the Cheka after her arrest. Tired face. Black, simple dress with some chalk stains, and a board on the neck with her surname written on it. I copied a photo and took it to her. It was the first time when she saw it. "And you see, the board is straight," she said. "He came to me and straightened the board before taking the photo. And the dress! You see? He smeared my dress with the chalk!" This what she said never came out of my mind and became a part of this picture. You cannot see the Cheka officer in the image, but he is captured there in this straightened board and chalk stains. This long story is to ask you – did you also find stories from or about the “curators” of these galleries in your research? Are the creators of the files somehow captured in the galleries or stories told by communities?

The use of the term ‘gallery’ in the context of our research on secret police archives was intentional as it was our aim not only to demonstrate that the images we find in the archives were indeed sometimes created, and then curated, for a specific audience and to achieve a specific end, but also through the project’s exhibition-making process, to demonstrate how the encounter in the gallery space can also serve as a research tool.

In the project, we have been dealing with different classes of materials, many of which were created by the religious communities themselves and then confiscated and inserted into files, but other materials were generated, as your story illustrates, to meet the requirements and achieve the aims of the secret police. The need to create the model mugshot for insertion into the file led to extreme cases like the one researched by Tatiana Vagramenko concerning a group of believers arrested in 1952 in the Kiev region of Ukraine. The file, which is featured in our online Digital Archive, contains two versions of their arrest photographs taken by the MGB officers, one in which the believers can be seen resisting the aim of the officers, intentionally closing their eyes, turning their heads away, or singing while the officers tried to restrain them with their gloved hands clearly visible in the images. The officers later tried to correct these “tainted” photographs by removing the evidence of their violent intervention from the prints, which one can see in copies of the same images with the hands of the policemen crudely shaded out (see Figure 3). These handless photos were used in the formal documentation of the case, while the smaller-size, original photos were consigned to the back of the file. Like the officer who straightened the chalkboard in your example, the images created needed to conform to a set of criteria but also to a certain aesthetic of the file.

So indeed, the images and files were created and curated for a specific purpose but the Hidden Galleries project aimed to do more than simply highlight these incongruous visual and material representations of religious groups in the files. Integral to the project design, and hence the choice of the term ‘galleries’, were the exhibitions we staged in Cluj-Napoca and Budapest, in which we took previously overlooked visual and material sources and in the gallery space created encounters between diverse publics, researched communities and the material created by and about religious groups. Through the collaborative process of exhibition making, the selection of objects and stories for the exhibition in consultation with communities became a tool of research in itself whilst the exhibition space produced a different quality of encounter for the researchers, our research participants and the public. The doctored mugshots discovered by Tatiana Vagramenko and subsequently curated by Gabriela Nicolescu and the project team for the exhibitions (see Figure 4), generated a whole series of new questions regarding the materials and their meaning and uses today that Tatiana and Gabriela have explored in a forthcoming article ‘The Hand at Work or How the KGB File Leaks in the Exhibition’ in Martor: The Museum of the Romanian Peasant Anthropology Review (forthcoming, 2021).

Our exhibitions in gallery spaces became a new arena of research that allowed us to engage communities, archival authorities and publics in questions related to access to hidden materials, and the preservation and ownership of lost or stolen aspects of religious patrimony. In the context of these additional questions of the ethics of display, the restitution of cultural property, and the role of museums and galleries in memory politics and the pursuit of the public good, the term ‘galleries’ proved extremely fitting for our research. Some of these points are explored in the project visual album, Hidden Galleries: Material Religion in the Secret Police Archives in Central and Eastern Europe, especially in the postface by Gabriela Nicolescu, the project curatorial lead, ‘Exhibitions as tools to think with: On impact and process.’

Original of the cover image: Surveillance photos of underground Greek Catholic bishop Ioan Dragomir, 1973. http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/item/233

Cite this interview: James Kapaló, “Hidden Galleries: Interview with James Kapaló,” Part 1, interview by Sanita Reinsone, Blog4Dissent, August 23, 2021. https://nep4dissent.eu/blog4dissent/hidden-galleries-interview-with-james-kapalo-part1