HIDDEN GALLERIES: Interview with James Kapaló. Part 2

The interview was carried out by Sanita Reinsone as an e-mail conversation from 7 July to 18 August 2021, without any haste or length limit.

23/08/2021

Read the Part 1 of the interview here.

The Hidden Galleries project involved exploration of the archives in at least four countries. The archival world might be very specific and rules for what can be accessed and published differ from country to country, especially regarding the information kept by the secret service archives of relatively recent past. How open and willing were these archives for collaboration? Did you find any difficulties? Were there any differences among the archives, i.e., how files are organized and what information is captured about religious communities?

The archival institutions with which we worked most closely, ÁBTL in Hungary and CNSAS in Romania, were very open and extremely helpful. The collaborations with these institutions went beyond our expectations and we are extremely grateful to the directors and research staff at these institutions. It is important to understand that in Hungary and Romania there is a fairly long-established framework within which researchers can access files and publish research based on their findings. In the case of ÁBTL, we built really good collaborative working relations with the in-house research specialists who went on to contribute to our publications and supported the research team in finding difficult to locate materials. The Secret Police Archive in Romania loaned equipment and created special copies of materials for the public exhibition in Romania and gave us their public support and endorsement. This is not to say that research in secret police archives in these countries has been without political controversy over the years or that all kinds of research have enjoyed equal levels of good will from these institutions but in the case of Romania and Hungary we were able to pursue our research without any real obstacles.

With regard to the Republic of Moldova, we had much more limited access to Soviet-era secret police materials. A Special State Repository (SSR) was created within the Intelligence and Security Service of Moldova in 1992 that contains the archival collection produced by the former Soviet secret police. This archive has not been declassified but limited access to its fonds was provided to a small group of some at different times after 1991. Fortunately for the project, in 2010 approximately 25.000 police investigation case files were declassified and slowly transferred to the National Archive of the Republic of Moldova, and since then these files have been accessible to researchers and to the wider public. This represents a considerable amount material that proved to be very rich in terms of religious items and images. The project owes a large debt of gratitude to Igor Cașu who pointed us towards this material and was able to copy some selected materials in advance of their transfer to the National Archive, giving us a good head start to what otherwise would have been a slow process.

The case of Ukraine is different again. It was as recently as 2015 when the SBU archive was placed under the jurisdiction of the Ukrainian Institute of National Remembrance, setting in motion the gradual declassification of its documents. The volume and types of materials available in Ukraine far outstrip what can be accessed in Moldova, and this proved extremely beneficial for the project, a fact witnessed by the richness and scope of materials from Ukraine assembled by Tatiana Vagramenko that we have been able to add to the Digital Archive.

The diversity and volume of visual and material religious items we found in the archives varied significantly from country to country but there were many similarities in way the files themselves were categorised and archived, which was based on the Soviet model. In Romania for example, the archive is divided into multiple fonds: Documentary Fonds on particular issues, including religion; Penal or Criminal Fonds, which consist of the trial documentation of those who were charged with crimes; Network Fonds, containing the files of people who, one way or another, collaborated with the Securitate; Informative Fonds of individuals who were under surveillance; and also importantly Manuscripts Fonds, which contain the materials confiscated by the Securitate. The Documentary Fonds reflect the policies and measures adopted by the Securitate towards religious communities and contain their orders, circular letters, statistics, reports, photographs, so on and so forth. The Informative Fonds, which include the surveillance files, also contain a wealth of information in relation to religious issues and individuals belonging to various religious communities. The main documents that could be found in such files are reports, notes from informers, intercepted documents (letters, manuscripts), (confiscated) photographs/materials, declarations. In the case of Romania, the Penal or Criminal Fonds proved to be the richest sources of religious materials as they often contain alongside all the interrogation notes, confiscated religious materials, confiscated photographs and personal letters. On the project Digital Archive homepage we have included this kind of description of the breakdown of files and their contents for all the major archives we consulted as an aid for researchers.

What we found, however, and not unexpectedly, was that the kinds of materials present in the various archives was very much shaped by the divergent histories and differences in the religious landscape of the countries we researched. So, for example, Stalinist-era Hungarian materials were very few and far between due to the destruction of materials that followed the 1956 Revolution. Because the large-scale repression of religious institutions happened before 1956, the archives in Hungary have relatively fewer examples of such materials. In the countries with large Orthodox population, we also found that visual materials, photographs and icons of religious leaders especially, featured heavily in confiscated materials. The secret police, it is clear in some cases, understood the power and role of images and material objects in the transmission of religion and also found these images and objects useful for constructing the image of the underground in anti-religious propaganda, something I have written about in a recent article.

James Kapaló is Senior Lecturer in the Study of Religions at University College Cork, Ireland and co-Director of the Marginalised and Endangered Worldviews Study Centre (MEWSC). He has an MA in Central and Eastern European Studies from the School of Slavonic and East European Studies (SSEES), London and a PhD in the Study of Religions from the School of Oriental and African Studies (SOAS), London. A specialist on religious minorities, his work draws on anthropology, folklore and history. He is Principal Investigator of the ERC Project Creative Agency and Religious Minorities: Hidden Galleries in the Secret Police Archives in Central and Eastern Europe (Project no. 677355).

To what extent were the communities you worked on the project aware of the materials that the secret police archives contain about them, were they curious about their fate?

As I mentioned earlier, the main objectives of the project were twofold: to shift the lenses of analysis on religion in secret police archives by making materials more readily available to scholars and by laying the conceptual groundwork in order to encourage and facilitate comparative research but also to engage descendent communities in questions of access and ownership of their lost patrimony. This aspect of the project has highlighted the very real bureaucratic and emotional obstacles that prevent or discourage ordinary citizens from requesting access to or repatriation of stolen religious items – I am talking about ordinary everyday items of low financial value that nonetheless often have important spiritual and personal meaning for individuals and communities. We began the discussion with communities about their views and hopes with regards to these materials, which we shared in the public exhibitions. Here are just a couple of examples of the (sometimes conflicting) views expressed by members of the communities we worked with regarding access to archives and the future use and ownership of objects we found there:

“They should be given back to the community, or at least given to museums that can preserve and exhibit them. The community should be the rightful owner of these items because it produced them, the believers made them. Not showing these items is not a right, it’s an abuse.” (Tudorist believer)”

“Archival materials are important because they reveal a lot of information about how things used to be for their community (…) I think these are extremely valuable for the younger generations. (…) They should be given back to the community because for the archives they are just objects of study, forgotten and covered with dust.” (Tudorist believer)

“It is important for these items to survive, to be preserved somewhere. If we are not able to do that, then they should be kept somewhere safe. I think that it is important for them to be honoured and for people to have access to them.” (Old Calendarist believer)

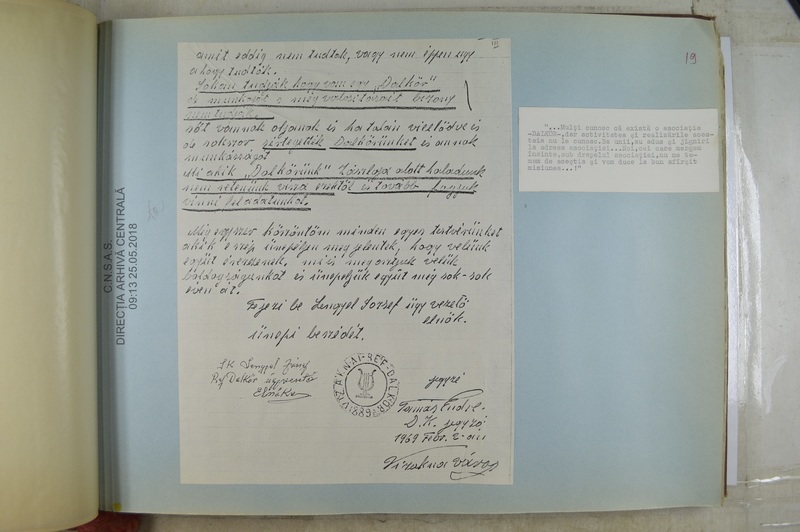

One of the stories researched by Ágnes Hesz that featured in our public exhibition in Cluj-Napoca and in the Digital Archive was really instructive in regard to this question. The Hungarian Reformed Church Choir from the town of Ocna Sibiului (Vízakna) was raided by the Securitate in 1973 and had its entire archive confiscated along with the official stamp of the choir (see Figure 5). As Ágnes explains in her research, although the choir was allowed to operate after the raid its members felt “robbed of its past” – since none of the confiscated items were returned. Some attempts were made to compensate for this loss, for example, several documents were recreated by the choir’s former secretary who, in lieu of the missing stamp, created a hand-drawn replica when necessary. Copying the stamp by hand was one way in which the choir coped with the loss of their belongings and an important symbol of its legitimacy, its stamp. During her fieldwork with the choir Ágnes asked their views on what should happen to stolen materials:

A: “The stamp should come home. It should come home. The stamp and the sceptre and the crown always stays with the king.”

B: “It’s a pity.”

A: “The stamp. It’s a pity that that stamp was lost because, how should I say it, it was a document, really.”

B: “A value.” (Members of the Reformed Choir, Ocna Sibiului)

Another member of the choir suggested instead that a replica should be created:

“An exact replica should be made, the replica should stay with us and the original should be preserved where it can be protected. This is my opinion… at least we should have the replicas.” (Member of the Reformed choir, Ocna Sibiului)

This aspect of the research proved fascinating and hopefully is just the beginning of a debate about the fate of lost cultural and religious patrimony hidden away in the archives.

CNSAS D 015847

An important phase of the study is finished now. How do you feel about that? Is the research of religious minorities and their relationship with the secret police finished or do you have new plans to continue?

It is a strange feeling to come to the end of such an exciting collaborative journey. I think I can speak for the whole team involved when I say that we have learned so much from each other over the years and shared so many experiences too, especially with regards to staging events and exhibitions. I feel profoundly indebted to the team, everyone worked together in a generous spirit to make it a success. This is no small feat, teamwork in the humanities and social sciences doesn’t necessarily come naturally in a system that demands that as individuals we build an individual, distinctive profile for our research.

What comes next? Well, I have a monograph in the pipeline on materiality and the transmission of religion during communism, and more research I would like to do on the secret police and anti-religious propaganda. There is also an ongoing collaboration that came about thanks to Nep4dissent, together with Tatiana Vagramenko, Selma Rizvic and the Sarajevo Graphics Group, we are enlarging and developing our virtual reality exhibition, The Underground. I aim to keep enlarging and enhancing the Digital Archive to include materials from additional countries, Poland in particular and we also have plans for further exhibitions in Ukraine and Moldova (which due to Covid restrictions have been put on hold) and publications of some of our key findings from the project in Hungarian, Romanian and Ukrainian languages. We will continue to post about all of this on the Hidden Galleries website: http://hiddengalleries.eu/.

Original of the cover image: Secret police photo album on a Hungarian Calvinist Church Choir Romania, 1973. http://hiddengalleries.eu/digitalarchive/s/en/item/195

Cite this interview: James Kapaló, “Hidden Galleries: Interview with James Kapaló,” Part 2, interview by Sanita Reinsone, Blog4Dissent, August 23, 2021. https://nep4dissent.eu/blog4dissent/hidden-galleries-interview-with-james-kapalo-part2